This could be my last post on this topic hopefully now as we enter 2023, and do the 40 detainees still held at Guantánamo

(Gitmo). Talk of closing it has lingered long enough – either try

them and put them in permanent prison, or set them free… nothing in between.

This

update from the Smirking Chimp with this headline as we and the

detainees head into the 21st year of their captivity as “Middle East War Captives:”

“Guantánamo: Will America's Forever Prison Finally Close On Biden's

Watch?”

The Beginning:

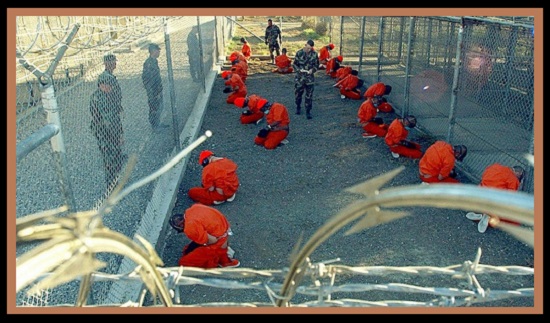

In January 2002, the first planes landed at Guantánamo, the hooded, shackled,

goggled, and diapered prisoners in them were described by the Pentagon at the times as: “The worst

of the worst.”

In truth, however, most of them were neither top leaders of

al-Qaeda nor, in many cases, even members of that terrorist group. Housed at Camp X-Ray initially in open-air cages

without plumbing, dressed in those now-iconic orange jumpsuits, the detainees descended into a void, with

little or no prison policies to guide their captors. Then Brig. Gen. Michael Lehnert (now retired Maj. Gen in 2009),

the man in charge of the early detention operation, asked Washington for

guidelines and regulations to run the prison camp, Pentagon officials assured

him that they were still on the drawing board, but that adhering in principle to the “Spirit of the Geneva

Conventions” was, at least, acceptable.

Those first 100 days left General Lehnert and his officers

trying to provide some modicum of decency in an altogether indecent situation.

For example, Lehnert and those close to him allowed one detainee to

make a call to his wife after the birth of their child. They visited others in

their cells, talked with them, and tried to create conditions that allowed for

some sort of religious worship, while forbidding interrogations by officials

from a variety of U.S. government agencies without a staff member in the

interrogation hut as well. Against the wishes of then Secretary of Defense

Donald Rumsfeld and the Pentagon, a lawyer working with Lehnert called in

representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

In March 2002, the U.S. installed prefab prisons at Guantánamo in which those

detainees could be all too crudely housed and had brought in a new team of

officers to oversee the operation while pulling Lehnert and his crew out.

The new leadership included people reporting directly to

Rumsfeld as they put in place a brutal regime whose legacy has lasted, in all

too many ways, to this day.

Despite General Lehnert's efforts, in the nearly 21 years

since its inception, Guantánamo has successfully left the codes of American

law, military law, and international law in the dust, as it has morality itself

in a brazen willingness to implement policies of unspeakable cruelty. That

includes both physical mistreatment and the limbo of allowing prisoners to

exist in a state of indefinite detention. Most of its detainees were held

without any charges whatsoever, a concept so contrary to American democracy and

legality that it's hard to fathom how such a thing could happen, no less how

it's lasted these 7,627 days.

Geo. W. Bush's

Prison: As the 40 prisoners still in Guantánamo illustrate, no

president has yet found a way to close that prison completely. George W. Bush,

who opened it, did eventually acknowledge that it would be best to shut it

down. As he said to a German television audience in May 2006: “I very

much would like to end Guantánamo. I very much would like to get people to a

court.”

He was, however, anything but decisive on the subject. As he

told a White House press conference that June: “I'd like to close

Guantánamo, but I also recognize that we're holding some people that are darn

dangerous, and that we better have a plan to deal with them in our courts. And

the best way to handle — in my judgment, handle these types of people is through

our military courts.” That month the Supreme Court invalidated

the ad hoc military tribunals that had by then been formed at Gitmo.

In the fall of 2006, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act (MCA), formally creating the

courts Bush had imagined.

Pointing out that shuttering the prison was not

as easy a subject as some may think on the surface, Bush began pursuing another approach — namely, releasing uncharged prisoners and

returning them to their home countries or transferring them elsewhere.

Bush and his administration did, in the end, release about 540 of the 790 prisoners held there with as accepted

its last prisoner in March 2008. Meanwhile, a

2008 Supreme Court ruling granting detainees the right to challenge

their detention by filing habeas corpus petitions in federal court opened a new

path toward future freedom. Twenty-three of those detainee petitions were

granted before Bush left office, but the prison, of course, remained open.

Barack Obama's

Well-Intentioned but Failed Efforts: Barack Obama initially signaled

his desire to close Guantánamo on the campaign trail and then, in one of his

first acts as president, issued an executive

order calling for it to be shut down within a year, writing: “If any

individuals covered by this order remain in detention at Guantánamo at the time

of closure of those detention facilities, they shall be returned to their home

country, released, transferred to a third country, or transferred to another

United States detention facility in a manner consistent with law and the

national security and foreign policy interests of the United States.”

With new energy, the Obama administration plunged ahead on

the two fronts Bush had halfheartedly pursued: establishing military

commissions and transferring certain prisoners directly to their home countries

or others willing to accept them.

On Obama's watch, a reformed version of the Guantánamo

tribunals was reauthorized by the passage in 2009 of the new MCA, resolving

five cases, all with guilty pleas. That administration edged toward closure and

transferred nearly 200 more prisoners to willing countries in a

vigorous effort over the final year and a half of Obama’s term.

Still, Obama encountered opposition within Congress.

Although the military commissions did start anew under Obama, so many years

later, the trial of the five prisoners alleged to have been

actual 9/11 co-conspirators has still not been scheduled – and that includes leader

KSM.

In addition, under Obama, numerous habeas corpus petitions

were filed in federal court, often falling victim to defeat in appellate

courts. As Shayana Kadidal, the Center for Constitutional Rights' senior

managing attorney for Gitmo litigation, summed it up at Just Security: “By 2011, the sharply

conservative D.C. Circuit rendered it more or less impossible for detainees to

prevail on their habeas petitions.”

Obama's team did seem to add a new possibility for aiding

the closure process by transferring one detainee to federal court for trial on terrorism charges.

In 2010, Ahmed Ghailani

stood trial in New York City for participating in the bombings of two U.S.

embassies in East Africa. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison

on U.S. soil.

But in the end, that trial proved fraught with problems, including the

fact that the defendant was acquitted on 284 of 285 charges and so it would

prove to be not just the first but the last such trial. In fact, in the 2011 NDAA, Congress included a ban on the transfer to the

United States of any further Gitmo detainees for any reason whatsoever.

All told, though the Obama

administration poured far more energy into the effort to close Gitmo than the

Bush administration had. In his last year, Obama continued to push hard with the rallying cry: “Let's go ahead and get this thing

done!”

He called for renewed

federal trials on U.S. soil and prisoner incarceration in the United States,

noting that Guantánamo was “contrary to our values and undermines our standing

in the world not even to mention the $450 million annual price tag for keeping

it open.”

Obama put the blame for failure squarely on the growing

political divide in the country and openly worried about what it meant not to succeed, saying: “I

don't want to pass this problem on to the next President, whoever it is.”

(And,

of course, we now know just who he was talking about: Donald J. Trump)

Donald Trump's “Bad

Dudes” policy: Not surprisingly, passing Guantánamo on to Trump

fulfilled whatever misgivings he had. Unlike Bush and Obama, Trump displayed no

interest whatsoever in closing it. His instinct was to reaffirm its standing as

a legal black hole. On the campaign trail in 2016, in fact, he swore: “We're gonna load it up with some

bad dudes, believe me, we're gonna load it up.”

(On taking office, almost instantly signed an executive order

to keep Gitmo open).

No new detainees were

actually added during his term in office. In 2020, Trump even suggested it should house people infected with CoVID,

but as it turned out, expanding its activities was as elusive a goal for Trump

as closing it had been for his predecessors.

While his threats of

adding inmates amounted to naught, his presidency basically put that prison camp

on pause. He even stopped the process of transferring five detainees cleared for release by the Obama team.

Only one prisoner, Ahmed

Muhammad Haza al-Darbi, who pleaded guilty in 2014 in the military commissions,

was released during Trump's time in office.

Meanwhile, the military commissions remained essentially stalled on his watch

and Congress continued the ban on moving any of the detainees to the U.S.

Now Biden's Gitmo: When

Joe Biden entered office in January 2021, 40 prisoners remained at Gitmo.

In his first weeks, his aides called for a formal review of

their cases and spokesperson Jen Psaki announced the Biden’s intention

to close the prison camp before he leaves office. Biden learned from Obama's

mistakes thus making no sweeping public promises.

His administration nonetheless put renewed energy into both

transfers and trials. The military commissions have indeed ramped up in recent

months. Pretrial hearings have recently been held in the four pending military

tribunal cases. In addition, plea deals that would take the death penalty off the

table are reportedly being negotiated for the five 9/11 defendants including KSM.

Three of the five

detainees cleared for release by the Obama administration have finally

been transferred to other countries, while all but three of

the 27 prisoners not cleared when Biden took office have been greenlighted to

go home or to a third country. In doing so, several previously blocked

thresholds were crossed.

As of early 2021, when the government cleared detainee Guled

Hassan Duran, it signaled that, for the first time, there was a willingness “to

release even those who had been subjected to torture while held at CIA black

sites in the early years after 9/11.”

The point was made even more strongly three months later

when Mohammed al Qahtani, who experienced some of the worst treatment at American hands,

was also finally released.

Meanwhile, in September 2022, President Biden appointed

former State Department coordinator for counterterrorism and former ambassador

to Kosovo, Tina Kaidanow, to oversee the transfer of prisoners cleared

for release. While her position doesn't replicate the formidable office of the

Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure that Obama established and Trump nixed, it

is a promising move. Her job of arranging each prisoner transfer, assuring the

security of the detainee, and assessing that the release will not pose a danger

to the United States is challenging but achievable, as prior releases have

demonstrated.

All told, recidivism rates for Guantánamo detainees,

as reported by the DNI, have been 18.5%, though only 7.1% for

those released under Obama.

The last question

after all these nightmarish years might be this: Are there any options

for the final Gitmo prisoners and closure of that place?

In 2017, military

defense lawyers Jay Connell and Alka Pradhan, joined by researcher Margaux

Lander, and pointed out: “That international law, victims

of torture, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment have the right to full

rehabilitation.”

In addition to seeking the removal of the death penalty in

their cases, the 9/11 defendants at Gitmo have reportedly asked for access to a

torture rehabilitation program.

Pradhan, who represents 9/11 defendant Ammar al Baluchi has summed the

situation up well: “The United States has utterly failed to give these men

either a fair trial or medical treatment for their torture in violation of

their legal obligations. Most of the evidence in the 9/11 case is

torture-derived, and the men are deteriorating quickly from the brain and other

injuries inflicted by U.S. torture nearly 20 years ago. The Department of

Defense has confirmed that they don't currently have the ability to provide

complex medical care at Guantanamo, so the most ethical solution is to transfer

the men to locations where they can obtain the care they require.”

In fact, after all these years in prison, releasing those

who might otherwise still stand trial and putting them in rehabilitation

centers might indeed be a good idea. There are many ways to address a wrong.

Arguably, the greater its magnitude, the more leeway should be given for

subsequent actions. As the Biden administration has taken steps towards closing

Gitmo, perhaps the gesture of sending the defendants in the military

commissions to rehabilitation programs is a good one.

For years, Gen. Lehnert

has told Congress, media outlets, and anyone who would listen that it remains

imperative, however difficult, to finally shut the prison down.

As he has written: “Closing Guantánamo is about reestablishing

who we are as a nation.”

It might not quite accomplish that, but it would certainly

be a formidable step in that direction. After all, its legacy of torture,

indefinite detention without charges or trials, and the reckless disregard for

the rule of law will no doubt haunt us for years.

There is no way to fathom the harm caused by the torture,

cruel treatment, legal limbo, injustice, and dehumanization that has become the

definition of Guantánamo. But for the first time in all these years, its actual

closure might realistically be on the horizon.

My 2 Cents: There is

nothing in this article that I disagree with and as an old interrogator myself,

I know and support the idea firmly that “torture does not work and is a serious

and unprofessional tactic for us.”

Yes, this post is long but comprehensive and

long overdue to reinforce the argument: Shut Gitmo down ASAP.

I say give those who need

a trial for their crimes justice and then punish them or set them free depending

after a fair trial and jury decision – that is the American way.

Holding them this long without

justice is just not right – imagine if North Korea or North Vietnam were still

holding our military POWs all these years behind bars in their Gitmo style

confinement? Serious question isn’t it?

Thanks for stopping by.